©2023 GWC Mag. All Right Reserved. Designed by Bami Design

PITTSBURGH — When Sandy Field first heard about the plan to build a new chemical recycling facility in her community in Point Township, Pennsylvania, she thought it sounded like a great idea.

“The plastic waste crisis is a real problem and I thought this sounded like a good solution,” she told Environmental Health News (EHN). “But then I went to the company’s open house and did some more research and I started to realize what a toxic process they’re proposing, taking 450,000 tons of plastic, melting it and making chemicals out of it right next to our river.”

The proposal came from Encina, a Texas-based company that hopes to build chemical recycling plants in the U.S., Mexico, Europe, Middle East and Asia. To date, the company has only recycled plastic at a small demonstration facility in San Antonio, Texas. The facility in Point Township, a suburban and farmland community of about 4,000 people, would be their first attempt to scale their operations.

Field, who lives about four miles from the proposed site, joined a campaign to stop the plant, citing concerns about air emissions and discharges of unregulated pollutants including microplastics and “forever chemicals”(commonly known as PFAS) into the Susquehanna River.

There are proposals in the works for similar chemical recycling plants across the country. According to a 2023 report by the nonprofit activist organization Beyond Plastics, 11 such facilities had already been constructed in the U.S. as of September 2023, with one closing this year.

The Encina site is part of a broader trend of proposed chemical recycling facilities in the Appalachian region. One of the more high profile proposed plants in Youngstown, Ohio, by SOBE Thermal Energy Systems, is currently on hold after the city passed a one-year moratorium on chemical recycling.

Experts say Encina and another proposed chemical recycling facility in Follansbee, West Virginia, are not geographic accidents. Appalachia and the Ohio River Valley are already home to a dense network of oil and gas infrastructure, including fracking and conventional wells, pipelines and a massive plastics plant. Chemical recycling facilities would represent a further expansion of this network, adding to the region’s overall burden of toxic pollution and continuing demand for fossil fuels and related infrastructure.

For example, in 2021, the nonprofit environmental advocacy group PennFuture reported that Pennsylvania subsidizes fossil fuels with an annual amount of $3.8 billion. The shale gas industry accounts for 52.1% of these subsidies, or $2 billion.

Jess Conard, Appalachia director of the nonprofit activist organization Beyond Plastics, lives in East Palestine, Ohio, and experienced the risks associated with living near this type of infrastructure firsthand last year, when a train carrying chemicals used to make plastic derailed and caught fire, poisoning the town.

“The chemicals that make plastic are very hazardous to our health, and when you transition the waste from a solid product to a vapor through advanced recycling, it’s not actually managing the waste,” Conard said. “It’s just changing the medium in which we’re exposed to these chemicals.”

“The river is a major focus of our lives”

Sandy Field kayaking on the Susquehanna River downstream of the proposed chemical recycling site.

Credit: Sandy Field

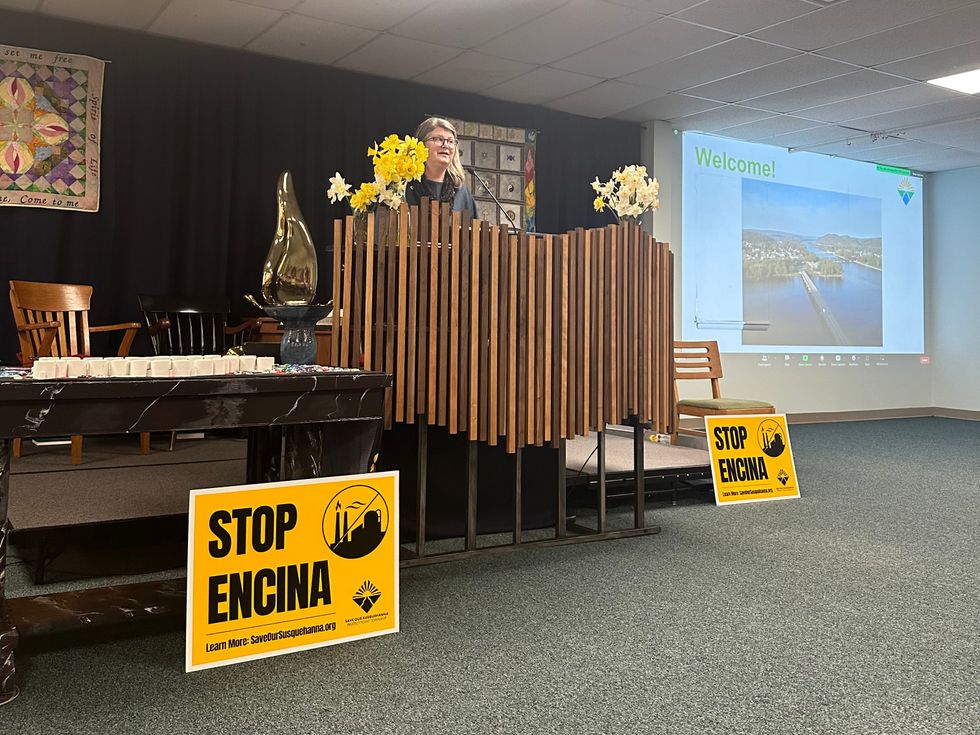

Sally Field speaking at our public meeting at the Unitarian church in Northumberland , PA, near the proposed chemical recycling site.

Credit: Sally Field

Encina’s proposed Pennsylvania plant would process up to 450,000 tons of plastic each year by melting them and using chemicals to break them down into substances like benzene, toluene and xylenes, which would then be sold to plastics manufacturers. The process also creates liquid oil products and solid hazardous waste. The company’s proposal included drawing as much as 1.7 million gallons of water a day from the Susquehanna River and discharging as much as 2.9 million gallons a day back into the waterway.

“The river is a major focus of our lives,” Field said. “We use it for recreation and fishing and we all drink out of it, and it’s really central to the character of the Susquehanna Valley.”

In an email, a spokesperson for Encina said the company would use “best-in-class technology” to remove pollutants and microplastics prior to discharging water into the Susquehanna and noted that their air and water emissions data would be public.

“The health and safety of our people and the communities in which we operate is our top priority,” the Encina spokesperson said. “We address community concerns through regular meetings and communications where we listen and discuss our plans for water treatment and protection.”

In October, Encina withdrew its permit application for stormwater management — which the company needs in order to start construction — after state regulators said it was deficient, but the company said it is still moving forward with plans for the site.

“The river is a major focus of our lives.” – Sally Field

Local officials have had mixed reactions to the proposal, with some welcoming the temporary construction jobs the project would bring to the region and others expressing concern about environmental health impacts. In 2020, former Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf signed into law a bill exempting chemical recycling facilities from having to obtain a solid waste permit. The Encina plant had already been proposed at the time and it remains the only proposed chemical recycling facility in the state, so the bill is seen as having been passed specifically to benefit Encina.

Pennsylvania is one of 24 states — including Ohio, West Virginia, Virginia, Kentucky — that have passed similar laws, which the American Chemistry Council has lobbied for, to reclassify chemical recycling facilities as manufacturing rather than waste facilities, which reduces regulatory oversight and makes it easier for these companies to obtain public subsidies.

Field sees Encina’s project as one of several “false solutions” being pushed by industrial interests in response to mounting concern over climate change and plastic pollution. A longtime climate activist, Field joined No False Solutions PA, a coalition of advocacy groups opposing chemical recycling, carbon capture, hydrogen energy and fracking.

Field co-authored a 50-page statement published by the group in January that decries these industries as “emerging technologies that claim to be solutions to the climate crisis but in fact exacerbate the climate crisis, damage the environment and/or harm public health.”

“We’d like to be talking about positive things, focusing on our renewable energy future, but instead we’re stuck playing whack-a-mole with every dumb idea that comes out of the fossil fuel industry as they decline and they’re just trying to stay in business,” Field said.

For Field, stopping Encina’s proposed plant represents the importance of taking a stand against these “false solutions” in Pennsylvania.

“This is the first advanced recycling facility being proposed in Pennsylvania, so we really feel an obligation to stop it,” Field said. “These false solutions would all take Pennsylvania in the wrong direction, moving backwards on our health and the environment.”

“Ask lots of questions”

The Better Vision for the Valley event put on by the Ohio Valley Environmental Advocates in October.

Credit: OVEA

Frank Rocchio doesn’t resemble a stereotypical environmental activist.

His shaved head and well-tailored suits are more in line with his decade-long career in the Secret Service and counter-terrorism intelligence in Washington, D.C., or his current role as a wealth management advisor.

But last year Rocchio and his wife founded Ohio Valley Environmental Advocates, a community advocacy group dedicated to stopping a proposed chemical recycling facility in Follansbee, West Virginia, about 40 miles southwest of Pittsburgh.

Rocchio grew up in Follansbee, and he and his wife moved back there a few years ago to raise their son and daughter, who are now six and eight years old, wanting to be closer to Rocchio’s parents and live at a slower pace. Their home is within a couple miles of Empire Diversified Energy’s proposed advanced recycling plant.

“‘Environmental’ is in our name but public health is really our main concern,” Rocchio told EHN. “This region is bleeding money. We’d like to welcome any industry that can bring in jobs, as long as that industry is being responsible and putting the health and safety of our community at the forefront.”

Initially, Empire Diversified Energy proposed a medical waste processing plant — which promptly drew opposition from the community. After ditching that plan, the company announced that it wanted to use a new “pre-pyrolysis process” to recycle plastic waste, which involves using heat and chemicals to break plastic products down into component parts.

But according to Rocchio, the company’s story just kept changing — from what they wanted to do at the plant to whether or not they’d require an air permit — and these incongruities created mistrust.

“Their answers to our questions kept changing and there were a lot of red flags, so my wife and I just started digging,” Rocchio said. They learned that the pre-pyrolysis technology the company intended to use is new and hasn’t yet been used at scale in the U.S., that the site would emit greenhouse gasses and toxic chemicals and that the plant was expected to create a maximum of 25 new jobs, according to Rocchio.

“We’d like to welcome any industry that can bring in jobs, as long as that industry is being responsible and putting the health and safety of our community at the forefront.” – Frank Rocchio

They also learned that the region was already home to numerous major air polluters and that Follansbee is in a valley prone to weather inversions that trap pollutants, so they worried about the cumulative effects of adding more toxic air emissions to that mix. They found the same stories about accidents and fires at other chemical recycling plants that prompted concerns about SOBE’s proposed plant in Youngstown.

Fofllansbee’s city council and mayor have asked Empire Diversified to meet with the community and answer questions prior to approving building permits at the site, with at least one councilmember saying he was uncomfortable approving these permits until he had a more comprehensive understanding of the company’s plan. Several public meetings have been held since then. Local union leaders have said the company might hire union members and expressed support for the project. Empire Diversified has filed an application for a state air quality permit from the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection that’s still under review.

“East Palestine was also a warning in terms of supportive infrastructure and emergency services,” Rocchio said. “We know they’d be trucking in, railing in and barging in feedstock and supplies for this plant, and we only have a volunteer fire department here.”

Empire Diversified Energy did not respond to a request for comment, but the company is still pursuing permits for the facility and says it intends to hold community meetings each month to increase transparency around its plans.

Roccio offered advice to other communities facing proposals for advanced recycling facilities.

“Ask a lot of questions,” he said. “Do your research. Especially if your tax money is subsidizing something like this, you need to ask how much money is likely to stay in the local economy and how many jobs will be created.”

“Seek out subject matter experts in academia,” he added. “They’re usually happy to get on the phone about these things and you’ll need technical expertise to be able to hold the people who are writing these permits accountable. Above all, don’t stop asking questions.”

We are a one-stop source for all things sustainability, featuring articles on eco-friendly products, green business practices, climate change, green technology, and more. Get the App now!