For the last couple of years, the Australian Energy Market Operator has been ramping up preparations for moments – or in its parlance “trading periods” – when the country’s main grid will reach “instantaneous 100 per cent renewables.”

According to AEMO chief executive Daniel Westerman, this “unparalleled” event was likely to occur as early as 2025, and AEMO launched an engineering roadmap to ensure that all the important grid services like inertia and system strength would be in place by that time.

But it now seems that while the “opportunity”, or the “potential” for instantaneous 100 per cent renewables will indeed occur in the next year, it’s now unlikely to actually occur until at least a decade later, when the last coal fired generator exits the system.

In the bowels of AEMO’s draft of the latest version of its multi-decade planning blueprint known as the Integrated System Plan there is Appendix 4, which focuses on system operability, which acknowledges that moments of instantaneous 100 per cent renewables won’t be happening any time soon.

And there are two main reasons. The first is that while the “potential” to reach 100 per cent renewables is nearly upon us, there are many reasons why some of that wind and solar output will be curtailed, by network constraints, or economic ones – such as negative prices.

And then there are the remaining coal fired generators. They won’t be switched off just to make way for wind and solar because, as a “baseload” generator, they don’t like to be switched off. And AEMO can’t tell them to, particularly not just to make a 100 per cent renewable headline.

“At the time of writing, NEM renewable resource potential has reached a high point at 99.7 per cent of demand across a 30-minute period,” it writes in Appendix 4, in reference to the peak that was reached on October 1 last year.

“By 2025, it is projected that periods of over 100% renewable potential (when hydro generation plus available VRE exceeds forecast demand) will occur regularly, particularly during lower underlying demand intervals,” AEMO says.

“As renewables replace thermal generation, the range of renewable potential experienced by the NEM becomes higher and narrower, and 100% renewable potential occurs more frequently at higher underlying demand levels.”

The graph above shows how the number of “potential” 100 per cent renewable events increase over the coming years.

“However, this does not mean these periods of renewable resource potential will result in instantaneous renewable

penetration of 100 per cent,” AEMO notes.

“Instantaneous renewable penetration outcomes are lower than renewable resource potential due market behaviours, network constraints, system security requirements and distribution network considerations.”

It says even by 2029/2030, when renewable “potential” is projected to be sufficient to meet all demand occasionally around one quarter of the time, the continued operation of coal-fired generators will prevent 100% instantaneous penetration from being achieved.

It says the generation mix is only forecast to reach actual 100 per cent instantaneous penetration in the NEM when the last coal units retire – currently scheduled for 2037 – and possibly earlier if seasonal withdrawal of coal capacity occurs.

It is possible that some coal plants, such as Bayswater and Mt Piper in NSW, may negotiate deals that allow them to operate on “seasonal standby” basis, which might mean they shut down over winter, but grind back up again to help manage peak demand in the summer heat.

That could occur, some analysts suggest, as early as 2030, but it remains to be seen if enough new wind, solar and storage capacity is built to allow that to happen.

What is likely to occur sometime soon is that “net” 100 per cent renewables will be achieved on the main grid, which is to say that renewables will over a trading period produce more than is required for grid demand, with the excess going to storage, such as pumped hydro and big batteries. But some coal will be burning in the background.

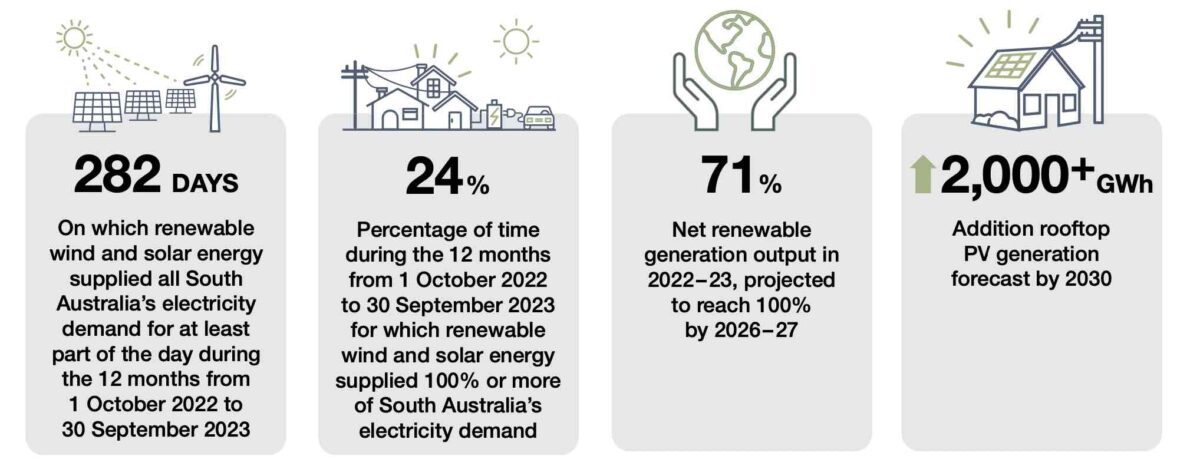

South Australia already achieves this on a regular basis – in more than one quarter of all trading periods over 2023 it produced more renewable, via wind and solar only, than it needed for local demand, according to the transmission company ElectraNet. (See table above).

The rest is either stored in its growing fleet of battery storage, or exported to Victoria.

It will soon be able to export to NSW as well when the new high voltage transmission link is connected, and by 2027 the state government expects the state to reach “net 100 per cent” renewables, meaning it produces enough wind and solar over the year to meet all of local demand.

That will make it the first gigawatt scale grid in the world to achieve that. It already leads the world with an average 75 per cent wind and solar, something the network says is attracting significant new industries to the state.

What will be interesting to see is if South Australia can reach moments of “true” 100 per cent renewables in its own grid, which will mean shutting down the remaining gas generators that currently ensure enough system strength and other grid services in the grid.

At times of high renewables, only around 80 MW of this gas fired generation is required. But with the new link to NSW, and with more batteries equipped with “grid forming” inverters that can deliver these essential grid services, then those gas generators will not be required to run at those times.