According to IEA figures, in 2019 the energy sector employed over 65m people, 2% of the global workforce. Half of that workforce is already in the clean energy sector, and demand for skilled employees is soaring. Whereas fossil jobs are heavily weighted to low skilled and very high skilled, most clean energy jobs are at the high end. Helena Uhde at Ea Energy Analyses looks at this new world, explains the differences, and notes that although there’s a predominance of jobs for “engineers” there are plenty of new jobs in HR, marketing, legal, project management, and more. The IEA is giving guidance on what needs to be added to the standard curriculum to make sure training for the new energy economy are in place, and what existing careers and skillsets can be easily transitioned into supporting it. Uhde also speaks to recruiters and jobseekers to illustrate how difficult it can be to match people to jobs when job title definitions, in these early days, are in constant flux and yet to settle down.

According to IEA figures, in 2019 the energy sector employed over 65m people, 2% of the global workforce. Half of that workforce is already in the clean energy sector, and demand for skilled employees is soaring. Whereas fossil jobs are heavily weighted to low skilled and very high skilled, most clean energy jobs are at the high end. Helena Uhde at Ea Energy Analyses looks at this new world, explains the differences, and notes that although there’s a predominance of jobs for “engineers” there are plenty of new jobs in HR, marketing, legal, project management, and more. The IEA is giving guidance on what needs to be added to the standard curriculum to make sure training for the new energy economy are in place, and what existing careers and skillsets can be easily transitioned into supporting it. Uhde also speaks to recruiters and jobseekers to illustrate how difficult it can be to match people to jobs when job title definitions, in these early days, are in constant flux and yet to settle down.

According to the IEA, the energy sector employed over 65 million people in 2019, equivalent to around 2% of the global workforce. The aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing conflict in Ukraine have led to fuel shortages, fluctuating energy prices and inflation. In the past few years, the global energy system has been in crisis mode. Yet despite – or maybe because of – the crisis, demand for skilled employees in the energy sector is soaring.

‘If you read the latest World Energy Outlook, the overall theme of the response to the conflict in Ukraine and the energy crisis is overwhelmingly taking us on a trajectory with more clean energy investment,’ explains Daniel Wetzel, head of the Tracking Sustainable Transitions Unit at the IEA. ‘In the short term, we are seeing a temporary resurgence of coal, but we’ve also seen that the surge in clean energy has mitigated that to a large extent. What that means for employment is that we are seeing an uptick of energy investment. That increase basically means a lot more jobs.’

Clean energy sector accounts for around half the energy workforce

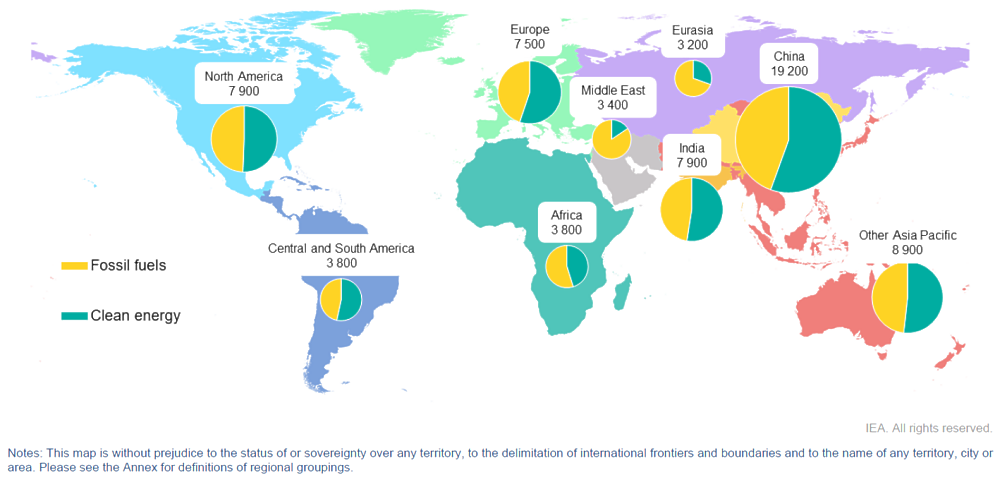

In September 2022, the IEA published the World Energy Employment report[1], a comprehensive inventory of the global energy workforce, mapping the labour force across regions and technologies. The report shows that regional distribution of jobs is concentrated in locations where energy facilities are under construction and where upstream components are concentrated.

For example, the vast majority of solar PV manufacturing is in China. In the EU, the REPowerEU plan, with its emphasis on energy efficiency, has increased the need for workers who can retrofit buildings. One of the key findings in the report is that about half of the global energy workforce is already in the clean energy sector. In the EU and in China, the figure has already surpassed 50% (see Figure 1). ‘This is driven by the fact that energy is an infrastructure-intensive industry with low operating costs, and it’s designed that way. So most of the jobs are going to be created in the development phase, whether that is manufacturing upstream components or building the actual plants,’ explains Wetzel, lead author of the report.

Figure 1: Energy employment in fossil fuel and clean energy sectors by region, 2019. / SOURCE: IEA, 2022

Highly-skilled technicians and engineers are in high demand

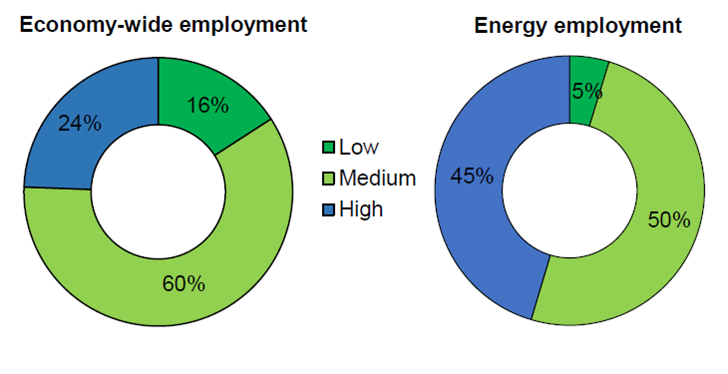

Compared to the average economy, the energy sector demands more skilled workers and in return offers higher wages. ‘Energy is an industry that requires a lot more high- and medium-skilled employees and very few low-skilled employees compared to the economy-wide average,’ explains Wetzel. ‘Engineers are highly skilled, and account for around 45% of the energy workforce. The majority of jobs are in the medium-skilled professions, such as wind, and solar plant construction, energy retrofits, etc. However, traditional energy industries are sort of on either side of this: coal mining includes a high proportion of low-skilled jobs in the developing world while oil, gas, nuclear, employ highly-skilled people who are predominantly engineers. Many clean energy technologies offer a lot more opportunities to people in construction and manufacturing.’

Figure 2: Global employment by skill level, 2019 / SOURCE: IEA, 2022

What skills in particular are needed now?

In order to understand how to fill the labour gap, it is important to understand precisely what skills are needed to drive the clean energy transition. Currently, the IEA is working on an iteration of its World Employment Report that aims to identify the skills that are in particular demand. ‘We are looking at the occupations that are most in demand in clean energy sectors and then ask what other industries have those similar occupations? If you take the general electrician certification, for example, how much additional training is needed to enable a general electrician to install a solar panel, versus installing a wind farm? How many more weeks of training do you need? How much more specialisation is needed to get them into that career? And what is the wage premium commonly associated with that?’ asks Wetzel.

Using natural language processing to access a bigger database, the results of the investigation will offer a list of the standard skills or standard certifications that the industry is looking for. ‘Ideally, for key markets, like China, India, the US and the EU, we are aiming to provide a list of certifications that are required along with how much time they will take to achieve. So, we can design the curriculum such that these clean energy technologies are included into standard electrician training, in standard engineering training, and so on,’ comments Wetzel.

Finding suitable candidates is challenging

The higher the skillset requirements, the more difficult it is to find suitable candidates. ‘It is fairly easy to find an ‘okay’ candidate. If the client is satisfied with 60%, we can fish someone out of our database rather easily. But to find the perfect candidate, we really need feet on the ground’, explains Qihan Geng, director of the China branch of the Green Recruitment Company, a British boutique recruiting firm that specialises in green energy and the clean technology sector. ‘If you ask the client to describe their ideal candidates, they will have a picture in mind: the right skill set, not a job hopper[2], innovative mindset, with experience related to the position and an interest in the job. Normally, that is not found in one person. Along the way, we are trying to make the client understand what is going on in the market, about the competitive package and transferable skill sets. It is also important to embrace current trends like remote working. Many of the traditional employers don’t really embrace these trends, but they have to adjust. And sometimes the position is so niche, that it is really rare that one person meets all the requirements,’ says Qihan Geng.

In China, it can be difficult for multinational companies to attract the best candidates, as Qihan Geng points out: ‘A lot of candidates with a commercial background are seeking careers in Chinese state-owned companies, because they think that those are better for their career in the long term. It’s not that multinational companies are not doing a great job, but they are not in favour among jobseekers.’

A little higher up the career ladder, the best candidates are often not even looking for a job: ‘About 60% of the time, the candidates are passive job seekers and do not actively put their profiles on LinkedIn or other job boards. It is our job to identify them as suitable for the role and to convince them to have a conversation. The rest are active job seekers, who reach out to recruiters like us. Only a small percentage are people that are referred to us’, explains Qihan Geng. ‘It’s part of our job to know where our clients are positioned in their marketplace. And then it’s easy to find people and companies related to their business, whether that is their direct competitors, suppliers or downstream-related businesses. Naturally, someone that is working in a related field has the right skill set to work for these companies. We need to understand the sector, accumulate enough profiles and candidates, and develop our own talent pool. With the right keywords and the right lens of experience, it’s easy to identify candidates. Of course, we also use external job boards and there is the traditional way of calling people and asking for referrals.’

Not just engineers! HR, marketing, legal, project management etc…

Just as it is difficult for companies to find the right candidate, it is a challenge for job seekers to find the right position. As a fresh graduate, it can be difficult to even know what roles exist. ‘When I was looking for jobs, I knew I wanted to work in the renewable sector, but I was constantly receiving results for engineers. And I thought, maybe this dream role that I want doesn’t exist,’ recalls Emma Darnell. Emma graduated with a MSc in Marine Ecosystem Management from the University of St Andrews in the UK in 2022 and is now working as an environment and consent specialist at Ørsted. ‘Your mind will often spring straight to engineering and technician roles, but there are so many roles that don’t require an engineering background. The development of a wind farm, for example, has so many different stages that are not just that final construction or the design of a wind farm. Similar to other office jobs, you do have HR roles, project management roles, and health and safety teams. Wind farms are slightly unique in the sense of having stakeholder and environmental teams, as well as market development, media and communications, and legal and finance teams. You do not necessarily need to have one specific background to be able to do really well and have new knowledge and ideas. It is such a new and developing field and it is great to have a diverse team and think about challenges in different ways,’ explains Emma.

In developing areas of employment, specific job titles are not always widely known. To find these niche roles, Emma has three suggestions: ‘Firstly, there are quite a few really good podcasts out there that give insights into different careers in the energy sector and upcoming research. Secondly, reading news articles is a good way to keep up to date with current developments and to find out about conferences, symposia and networking events. Thirdly, LinkedIn is such a good way of reaching out to people. Search the company name that you’re interested in and then see what roles other people have. Then it is so much easier to use those terms to search for positions. Everyone I contacted was open to having a chat. It is good to get a bit more insight into what their day-to-day is, because a job title or description can’t always give you that much of a clear picture of what someone actually does.’

In the end, talking to a person in the role helped Emma to find her dream role: ‘During my Masters, I worked on a project which involved looking at the impact of wind farms on bird populations, which sparked my interest. And I was thinking, maybe there is a career in this as well. I got in contact with a former graduate working at Ørsted as an environment and consent specialist and she introduced me to this role, which I thought was perfect. It marries up my interests of marine biology and the human aspects of working with stakeholders, and understanding policy.’

There is no doubt that as the clean energy sector develops there are enormous opportunities for medium- and highly-skilled workers. It is now the task of training establishments, recruitment firms and energy companies to ensure that the brightest new entrants to the workforce are able to identify those opportunities and enhance their skill sets so they can join in the drive towards net zero.

***

Helena Uhde is a Consultant at Ea Energy Analyses, and former Junior Postgraduate Fellow at the EU-China Energy Cooperation Platform

This article was first published in the EU-China Energy Magazine – 2023 September Issue, available in English and Chinese, and is published here with permission

REFERENCES

- IEA (2022). World Energy Employement. https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-employment?utm_content=buffer74b3a&utm_medium=social&utm_source=linkedin.com&utm_campaign=buffer ↑

- Here defined as someone who changes jobs within less than a year. ↑