EU industrial companies affected by the big changes to their carbon costs that come from the new EU ETS rules and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) must create strategies to deal with them, if they haven’t started already. Otherwise they will fall behind those that have. Pablo Ruiz at Rabobank summarises their analyses and conclusions. Ruiz presents a map for each of the different starting positions. The study looks at the critical industrial decarbonisation variables: carbon and energy intensity, investment options, and the expected effects of the CBAM on sectorial trade patterns. It illustrates how different strategies for carbon allowance purchasing and/or decarbonisation investments may or may not harvest significant savings against a business-as-usual scenario. The timing of decisions and pathways are crucial, and the analyses cover the period from now to 2030. Companies must assess where they stand in relation to competitors and, potentially, new competing sectors. And at the EU level, successfully managing the decarbonisation of industry can unlock profound growth opportunities for a European Union searching for its place in a constantly moving world, says Ruiz.

EU industrial companies affected by the big changes to their carbon costs that come from the new EU ETS rules and the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) must create strategies to deal with them, if they haven’t started already. Otherwise they will fall behind those that have. Pablo Ruiz at Rabobank summarises their analyses and conclusions. Ruiz presents a map for each of the different starting positions. The study looks at the critical industrial decarbonisation variables: carbon and energy intensity, investment options, and the expected effects of the CBAM on sectorial trade patterns. It illustrates how different strategies for carbon allowance purchasing and/or decarbonisation investments may or may not harvest significant savings against a business-as-usual scenario. The timing of decisions and pathways are crucial, and the analyses cover the period from now to 2030. Companies must assess where they stand in relation to competitors and, potentially, new competing sectors. And at the EU level, successfully managing the decarbonisation of industry can unlock profound growth opportunities for a European Union searching for its place in a constantly moving world, says Ruiz.

This is the last of three articles analysing the impacts of the updated EU carbon policy on industry and its trading environment. The first showed how the end of free carbon allowances given to EU industry will likely increase companies’ carbon bills substantially. The second looked at how much protection from carbon-intensive imports CBAM will give to EU industries.

- This article marks the concluding chapter of our trilogy analysing the transforming business environment that industries under the European Union Emissions Trading System face.

- It is an existential period for EU industry, as carbon policies are set to get really serious in the middle of a global geopolitical shift.

- The carbon intensity of EU industry will become a heavier and heavier burden driven not only by the new EU carbon policies but also by structurally higher energy prices.

- Navigating these challenging times will require strategic awareness of where companies stand in relation to their competitors and, potentially, new competing sectors.

- It is essential for companies that want to find, keep, or widen their position in a decarbonising industry to develop an in-depth understanding of their carbon strategies, the associated challenges, and the underlying opportunities.

- We propose a map for each of the different starting positions that industry firms can find themselves in by looking at critical industrial decarbonisation variables: carbon and energy intensity, investment options, and the expected effects of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism on sectorial trade patterns.

- From this perspective, we categorise EU industry players’ starting point as in the eye of the storm, on top of the wave, or driven by the undertow.

- We also illustrate how different carbon rights purchases and/or decarbonising investment strategies may or may not harvest significant savings against a business-as-usual scenario.

Industrial carbon strategy: from window dressing to lifeline

EU carbon policies are far from being the only source of change for EU industry. Geopolitical, regulatory, market, and financial forces are converging to trigger a technological shift of a size not seen since the industrial revolution. EU companies are urged to understand the new surroundings as they unfold and whether traditional entry barriers are being diluted or wiped out. Every industry player is going to be affected, one way or the other.

Under the “traditional” competitive pressures, relevant forces of change bloom. Think of increasing restrictions in the transport and global supply chains, ongoing or incipient trade wars, or rising concerns about the spread between input costs. While such dynamics, under what we term a “post-globalisation economy,” may become equally or even more relevant than the new carbon policies in the middle term, they exceed the scope of this article.

Focusing on the carbon-related change forces, we see that what used to be the more complex battlefield of the biggest players must now permeate the thinking of every company covered by the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS). Our first article assessed the potential increase that median companies in key industrial sectors can expect in their carbon bills for their emissions under a business-as-usual scenario. In our second piece, we described the different ways in which the new EU industrial carbon policies may affect the competitiveness of EU ETS-covered companies and, as a result, trade.

A framework: how and when to decarbonise

Ultimately, if companies want to remain active, they need to decide how and when to decarbonise. In this article, we propose a framework to guide companies as they design their answers (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Building a corporative decarbonisation path

We begin by outlining three different types of starting positions from which companies may face industrial decarbonisation, based on key carbon variables and the expected impact of the new EU carbon policies. According to our proposal, firms may find themselves starting in the eye of the storm, likely to be dragged by the current, or surfing on top of the wave. Each type can benefit from a different weighing of the context. We discuss their trademarks and, to complete the overview of choices ahead, assess which savings companies can realise in their carbon bills through several basic strategies.

With both elements in mind, we conclude by discussing the particularities of each starting position’s decarbonisation decision-making process. We then wrap up with a summary of this series of articles to clarify the essential perspective on the EU’s industrial carbon policies to help companies navigate the changing tides, at least its carbon currents.

Decarbonisation pathways: three main starting points

Companies should develop an awareness not only of their future decarbonisation challenges, but also those of their competitors and connected sectors. There will be as many decarbonisation processes as there are companies. But by looking at certain variables, one can identify common threads and patterns that can prove an insightful frame for any decarbonisation strategy. Valuable data for this purpose (such as the carbon dioxide emissions intensity of key industrial sectors, or metric ton CO2/metric ton product) is publicly and widely available from leading organisations, such as the World Economic Forum, the International Energy Agency, and the Joint Research Center.

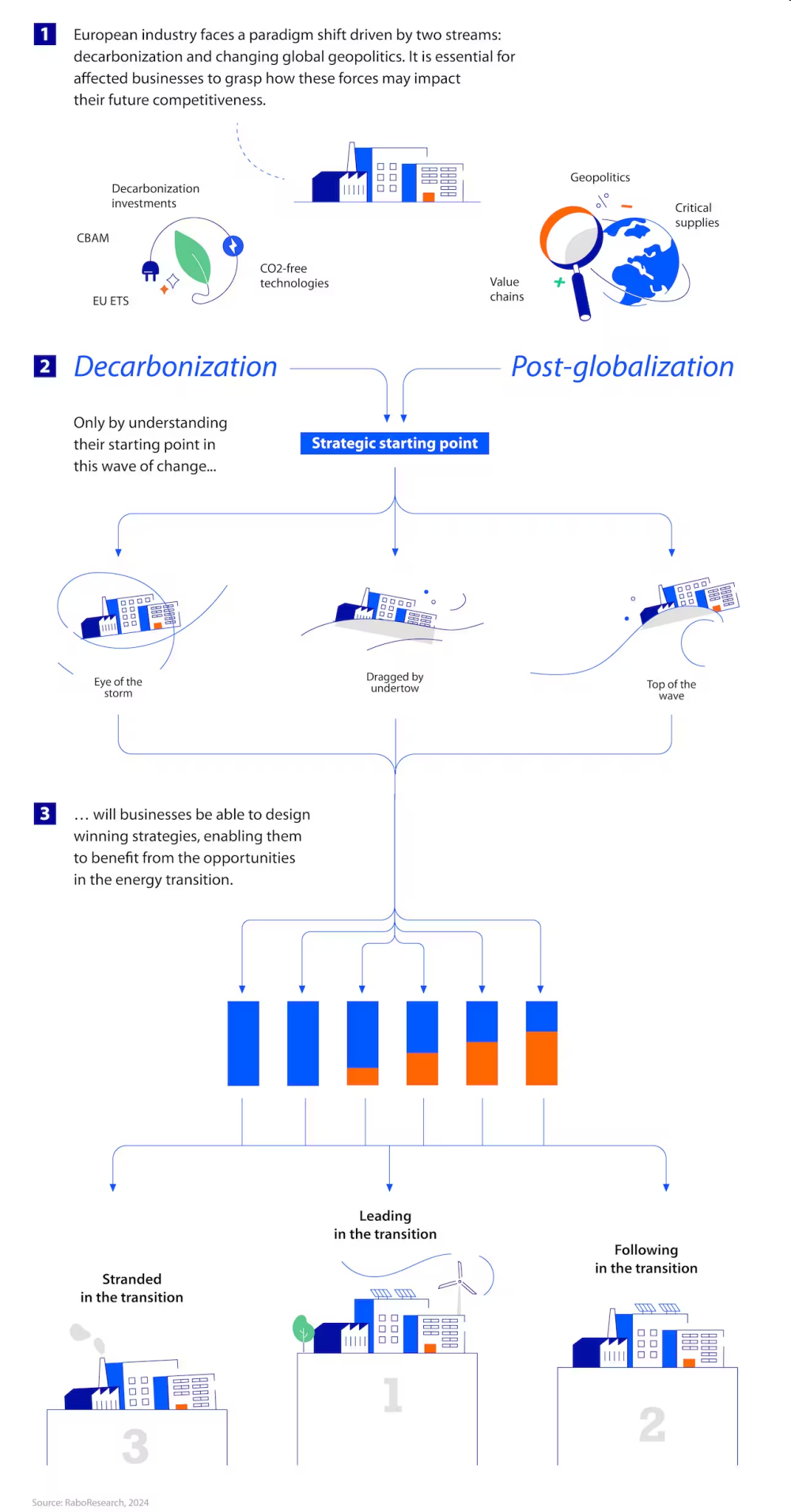

More specifically, by exploring the carbon and energy intensities (the main drivers behind the expected increase in corporate carbon bills) and the likely effect of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on the sector’s trade patterns, and by contrasting both of them with the available decarbonisation investments, we can distinguish three main starting points and subsequent decarbonisation processes:

- In the eye of the storm. This is the typical starting point for companies and sectors with the highest carbon (and energy) intensities, such as the average 4 tCO2/t aluminum of the aluminum industry. Those plants with process-related CO2 emissions face steeper decarbonisation trajectories,[1] that coupled with a significant reliance on exports will exacerbate the challenge. Policymakers have made efforts to prevent trade-related carbon leakage through the CBAM. How effectively it supports European industry will depend on the relative carbon intensities of EU players versus exporters, as analysed in the second article of this series.

Decarbonisation can also start in the “eye of the storm” for those sectors navigating the current environment of high energy prices fairly well by leveraging on previous EU and national support schemes or benefiting from the recent relative easing in energy markets. In particular, those with significant carbon and energy intensities should not dismiss the underlying carbon-related dynamics that they will soon face.

Companies starting in this situation need to devote substantial attention to defining and implementing their strategies well in advance to earn a chance to remain competitive.

- From the top of the wave. Companies may find themselves at the “top of the wave” if they have less prominent, but still significant, CO2 intensities, such as those found in iron or fertiliser manufacturers (both industries emit around 2 tCO2/t of output). Companies in these circumstances can typically expect a variable degree of protection against carbon leakage through the CBAM.

These sectors can typically choose among several technologies, depending on whether they have process emissions or not. Identifying successful examples of how early movers capitalise on the advantages of their investments can be essential to avoid being left behind.

For this group, competitiveness isn’t immediately questioned, nor is there an immediate need for decarbonisation. But, since decarbonisation still certainly needs to happen at a fast pace to sustain competitiveness, it requires significant preparation. The timing of decarbonisation investments can be the determinant of a hit and a miss.

- Undertow driven. Finally, companies with the lowest energy and carbon intensities (such as the cement industry, with an average carbon intensity in the EU of around 1.2 tCO2/t of output) may find themselves dragging their feet. As in the cement case, low reliance on extra-EU exports reduces the criticality of carbon leakage protection.

Players at this starting point may be the only ones that can afford to be more gradually “dragged by the undertow” to decarbonise. Such players can monitor the impact of rising carbon prices to decide on the optimal investment point. For industries with process emissions, carbon capture and storage solutions will likely be the default choice when the pressure from the carbon bill can no longer be absorbed.

The players standing on this ground must pay special attention to cross-sectorial competition. The lower immediate decarbonisation investment requirements can also be read as lower entry barriers that close competitors may explore. Leading players must be able to handle the relatively lower investment pressure in order to maximise the benefits that it harvests when inevitably done.

Table 1: Landscape of industrial decarbonisation positions / SOURCE: Rabobank 2024

Ways around the carbon bill

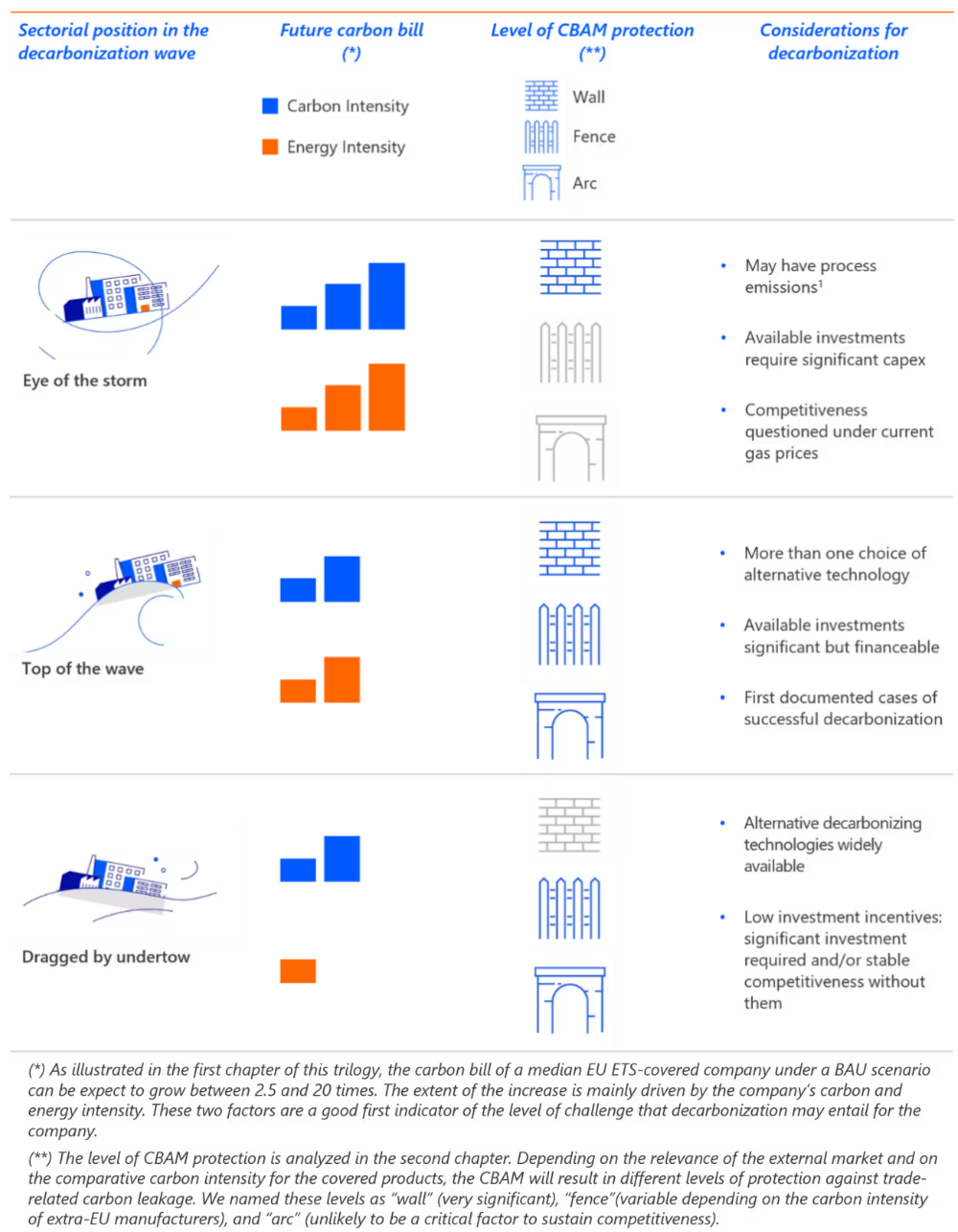

While critical investment decisions to be taken by industry players pile up, the ironing out of small details may result in a later decisive advantage. For example, in our view, an optimised carbon-purchasing strategy should be considered by any company affected by EU industry carbon policies. To illustrate the relevance of such an approach, we have tested the savings that different carbon strategies might achieve.

Consider the EU ETS corporative bill for the 2023-2030 period for an example company. Let’s call it the business-as-usual or “BAU bill.” The BAU bill includes the expected value of the EU ETS carbon emission rights (called EU allowances, or EUAs) that our example company will need to purchase to sustain its activity under the “BAU scenario” every year throughout the 2023-2030 period. The BAU scenario implies a continuity of the pre-Covid activity levels without any decarbonising investment happening and the implementation of the just-approved phaseout of free EUAs, as described in our previous article. We have tested the effects of two types of strategies:

- Forward purchasing: The most cautious and obvious approach is to annually buy or secure a percentage of excess rights, on the top of those required every year, to also cover the next period. In an EU ETS market with a highly probable upward trend, call options[2] may be an easy route to optimise the timing and cost of the orders, shaving a part of the carbon bill as a result. We tested strategies ranging from a 30% to a 100% yearly excess of purchasing orders, placed consistently along the entire 2023-2030 period.

- Early movers. Under this more ambitious approach, we model the assumption that the decarbonisation investment is swiftly decided for a given year ahead. To simplify the analysis, we also assume that such investment would stop all the operational emissions of the company. The company can then already decide in 2024 to buy in advance and in one lump all the EUAs required to keep BAU operations until the decided investment point. This approach delivers two routes for savings: unit price and total volume. Price-wise, if the emission rights are bought early on, they will be cheaper than if bought in the future (assuming increasing carbon prices, as described before). When it comes to volume, the earlier the decarbonising investment, the bigger the share of the required EUAs that will still be obtained for free. Moreover, if the investment happens before all free emission rights are phased out, the excess EUAs can be sold to support the decarbonisation investment.

We ran a scenario analysis comparing the potential reductions in the example company’s carbon bill for the 2023-2030 period from the two types of strategies relative to the BAU bill (see figure 2). Forward purchasing was tested at 30%, 50%, and 100% excess rights acquired annually, and early movers were tested for decarbonisation investments carried out in full in 2030, 2028, 2026, and 2025. Companies following the latter strategy could benefit from two saving components: a reduced price for anticipated EUA purchasing (dotted blue) and a volume reduction in the credits that the company would be required to buy (dotted orange).

Figure 2: Example of different hedging strategies’ potential to reduce the full 2023-2030 EUA bill / SOURCE: European Commission, BNEF, Rabobank 2024

In view of figure 2, some qualitative and tentative conclusions can be drawn regarding purchasing strategies:

- Forward purchasing at a fixed rate annually shows accumulated savings for the period are modest percentage-wise. Savings on the total bill following these strategies remain below 10% of the total BAU bill.

- Early movers’ strategies seem likely to result in more significant savings. However, as illustrated in figure 2, most of the savings are due to the reduced volume of EUAs needed. Since EUAs will be fully priced and are therefore expected to become more expensive toward the end of the 2023-2030 period, the earlier the investment, the bigger the savings for the whole period. This early mover’s approach can save from 30% up to 80% of the BAU bill along the reference period. However, should the EUA price unexpectedly decline substantially, these potential savings would be reduced.

It should be noted that both purchasing and hedging strategies should be carefully considered, as there are also risks associated with them. The most prevalent one is that the actual price of future EUAs turns out lower than what a company hedged against. We do note that most trends point toward an upward price curve for EUAs in the medium term, which might make hedging a relatively safe option in this case. However, as recent events in the UK illustrate, policy changes can alter the direction of a policy-dependent market. The purpose of this exercise is to illustrate the importance of understanding how different strategies influence results and decision-making processes. Firms should conduct their own assessments tailored to their unique conditions and not limit themselves to the proposed approaches here.

To decarbonise, or not to decarbonise… yet?

Once the choices for industrial decarbonisation are well understood, foresight analyses, such as those described in our previous articles, will frame the decision-making process for how and when to decarbonise. Naturally, such decisions will differ depending on the starting point:

- Players in the eye of the storm face existential decisions. Exiting or offshoring may be on the menu in the most critical cases. The relevance of and significant lead times for this group’s investments require an early launch of strategic reflection. For this group of players, the dynamics described in this article shouldn’t be news by now.

- The decarbonisation wave surfers have some precious margin to maneuver since their competitiveness is not immediately (or already) questioned, provided they don’t have to deal with process emissions. This time to think should not be wasted. On the contrary, industrial decarbonisation may swiftly turn from an investment and business opportunity to a life-threatening disaster if a solid strategy doesn’t guide the times ahead.

- Finally, those dragged by the current may be tempted to continue learning from the strategies of those more pressed to decide. They should, however, not forget that, in light of transformation processes, weak or late planning can act as an unpredictable current with the power to drag players to unexpected, undesired shores.

It’s the carbon, stupid! Well, that… and all the rest of the global mess

As described throughout this series of articles, recent regulatory, technological, and geopolitical events cast a wave of unavoidable change over European industry.

One of the main elements of this change on the way to 2030 will certainly be the expected EU ETS-related increasing cost for EUAs. We have illustrated what the financial impact of the proposed regulation could look like and how it may differ across sectors depending on their critical driving factors. While there are common considerations for industrial subsectors as a result of these driving factors, the subsequent decision-making will define what the process results in for each industrial player.

The pricing of carbon in the EU will also affect the trade competitiveness of EU industries. The CBAM may provide some shielding against more carbon-intensive imports from outside the EU. We have also analysed how this regulation may or may not shape industrial players’ cross-border trade balance. The CBAM might not provide the desired protection in all instances.

Weighing the impact of the EU ETS and the CBAM, we have sketched three types of starting positions for industrial decarbonisation. Common grounds can be identified across industry players based on their carbon and energy lock-ins, their trade patterns, and the appeal and maturity of the available decarbonising investment options. This article has provided guidelines to contextualise the decision-making for each type of situation, explaining the types of dynamics that the different markets will go through in the coming years.

Finally, we have illustrated the convenience and potential expected return for different carbon-purchasing strategies in the 2023-2030 period, working under the assumption that the price of EUAs will continue to increase. In general, in a context of increasing prices, hedging looks like a highly useful complementary tool for those affected by the EU ETS and CBAM, though players shouldn’t forget there are also risks associated with it. Forward purchasing strategies seem to lead to a lower level of potential savings versus early direct investments in decarbonisation. Such assessments can help fine-tune the timing of certain investments.

Combining all these elements together results in an overview of the way ahead that no industrial player can afford to ignore. European industry has extremely dynamic years ahead. Internally, the transformation is unavoidable in the current climate and political context. Externally, the survival of an essential element of Europe may be questioned, depending on how geopolitical events develop and, in a broader sense, how Europe finds its place amid the ongoing repositioning.

The decarbonisation of European industry is far from a simple isolated puzzle that one can easily assemble. Its resolution requires structured thinking as an essential ingredient for success. Decarbonisation is also not the only dynamic that will define the outcome of the transition. In this series of articles, we have illustrated how to deploy the “new carbon-related” strategic factors, but traditional ones (such as transport and global chains, trade wars, spread between input costs, and the impact of climate change on commodities’ yields) will continue to define the playing field. Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy amid post-globalisation extends the need for strategic thinking that considers all systems and encompasses the whole economic development and welfare of Europe.

A poorly managed transition may seriously affect the survival of a critical element of European wealth and employment, but properly heading the decarbonisation of the economy can unlock historical growth opportunities for a European Union searching for its place in a constantly moving world.

***

Pablo Ruiz is a Senior Energy Transition Specialist at Rabobank

This article is published with permission

REFERENCES:

- A company’s carbon lock-in can be structural if it’s a chemical result of their production processes, such as the extraction of calcium from limestone. These are the referenced “process emissions.” ↑

- Call options are one of the basic hedging tools. They are essentially financial contracts providing the right to buy a certain product (EU ETS emission rights in this context) at a certain price, at a certain point in time. ↑