The EU and its Member States are building out interconnectors to improve security of supply and affordability of electricity through the physical and economic linking of national energy markets into a single, synchronised European market. But each interconnector is expensive, complex and therefore risky. They can span long distances or natural obstacles such as mountains or seas. Significant network planning and adaptation is needed to account for the additional capacity when different markets are connected. Jean-Baptiste Vaujour at the Emlyon Business School reviews the landscape, and surveys the different ways interconnectors are being financed. The usual revenues, mostly congestion charges, are particularly risky: they are exposed to market developments on both sides of any border and to changes in price volatility as the penetration of renewables rises. Vaujour looks at the incentives and policies that have been deployed to reassure and attract investors, both public and private.

The EU and its Member States are building out interconnectors to improve security of supply and affordability of electricity through the physical and economic linking of national energy markets into a single, synchronised European market. But each interconnector is expensive, complex and therefore risky. They can span long distances or natural obstacles such as mountains or seas. Significant network planning and adaptation is needed to account for the additional capacity when different markets are connected. Jean-Baptiste Vaujour at the Emlyon Business School reviews the landscape, and surveys the different ways interconnectors are being financed. The usual revenues, mostly congestion charges, are particularly risky: they are exposed to market developments on both sides of any border and to changes in price volatility as the penetration of renewables rises. Vaujour looks at the incentives and policies that have been deployed to reassure and attract investors, both public and private.

This article is the third in a series of four articles by Vaujour dedicated to the development of electrical interconnectors in Europe. The first article discussed the economics of the sector and its important contribution to security of supply, electricity affordability and emissions reduction in Europe. The second looks at Eleclink, an innovative private interconnector.

The investment conundrum

Investing in interconnection capacity has long been dominated by public utilities. Until the opening of energy markets in the 1990s, interconnectors were only seen as a way of providing back-up supply and to strengthen security of supply. Two parallel phenomena have since then led to a shift in paradigm. First the increasing penetration of intermittent production from renewable sources leads to local surpluses that either require curtailments or need to be exported to other markets. Conversely, local shortfalls in available power require imports to maintain the continuity of supply. Secondly, these situations generate significant discrepancies in power prices between different markets.

Interconnectors answer these two stakes through the physical and economic linking of national energy markets into a single, synchronised European market. The only limiting factor is the available capacity of the interconnectors, as a finite amount of energy may transit through them at any given time.

However, building interconnectors is not a straightforward task. These assets often involve crossing long distances or natural obstacles such as mountains or seas. They are technically complex, notably requiring significant network planning and adaptation to accommodate for the additional capacity.

As the recurring delays in their authorisation and construction processes demonstrate, undertaking the deployment of a new interconnection is a risky endeavor. This is a key element of the economics of the interconnector industry. Although they are transmission assets, their risk profile is significantly different from that of traditional grids. This divergence is further reinforced by the commercial risk to which they are exposed, as their revenues are largely driven by congestion charges. These charges in turn are exposed in the long run to market developments on both sides of the border and to changes in price volatility due to the increasing penetration of renewables.

From a financial perspective, this means that if their compensation structure is identical to that of the other assets in a TSOs’ balance sheets, then the risk is not adequately compensated for investors. It also means that the rest of the balance sheet is indirectly subsidising these assets, providing cash buffers should the interconnectors not respect their business plan.

As can be seen in the table above, compensation levels for traditional TSO assets, both in terms of weighted average cost of capital (WACC – the average rate of return for debt and equity providers) and cost of equity (for equity only) are consistent with low-risk activities. Average performances of infrastructure funds are noticeably higher[1].

Two options

This creates a conundrum where TSOs are not compensated enough to undertake these investments. They then have two options. First, if the TSO is state-owned, public authorities may decide to proceed with the investments and to drown them in the general mass of the TSO’s balance sheet. It has long been the preferred option as interconnector projects were limited both in scope and in number. However, with the ambitious European grid expansion plans, this becomes increasingly risky as unexpected developments in project delivery may divert significant resources towards interconnectors that would have been required elsewhere.

The second option is to allocate specific resources and compensation premiums for these assets for them to be attractive enough for investors and to avoid cross-subsidies.

The structural commercial value for interconnectors rests in the congestion charge they can levy on electricity flows. In a regulated regime, this value is deducted from the network tariff (as in the French TURPE) so that the TSO does not get a double compensation for the asset. However, this revenue stream is insufficient to provide the required level of profitability for the project. This has been addressed in different ways: new financing sources have been created to reduce the total cost of the asset, regulations have been introduced to improve the revenue flows and additional revenues have been allowed.

Finding new financing sources

Deeply aware of this financing issue, the European Commission has worked on two mechanisms to provide direct financing to interconnection projects.

The Trans-European Network (TEN-E) regulation in 2013 and its revision that came into force in 2022 have identified priority corridors and created a regime for Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) that may benefit from direct funding from the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF). Up to €5.84 billion has been flagged for the 2021-2027 period for these projects, among which interconnectors are included. The aim of the Commission is to bridge the gap between the total social benefits of these projects and the commercial value that can be extracted from them by providing public financing. The PCI funding may finance the studies and part of the work itself.

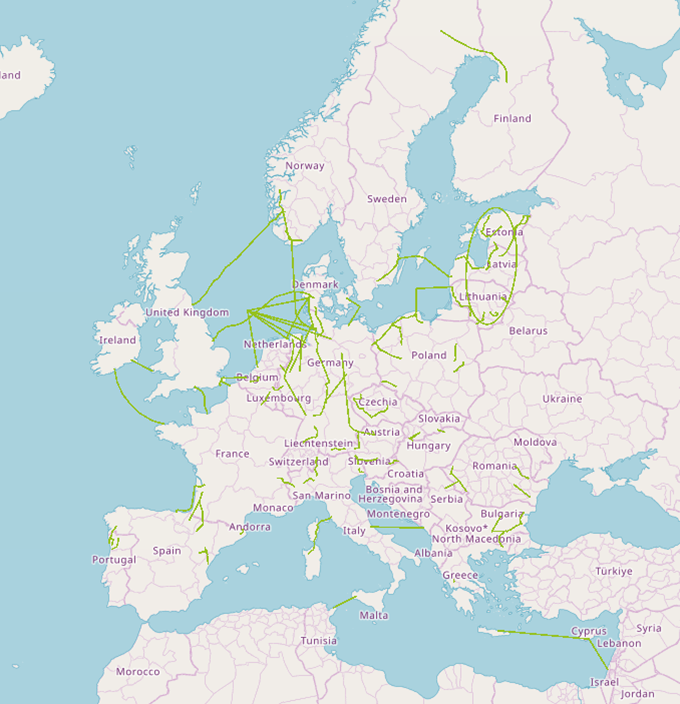

Map of electricity transmission lines in the PCI regime / SOURCE: European Commission, CINEA, PCI Transparency Platform, retrieved 17/03/2024

At the same time, the European Investment Bank has been solicited to continue providing debt financing to these projects. The Bank updated its lending policy in 2019 to reflect this priority and frequently commits significant amounts to interconnectors projects within the PCI framework. For example, it proposed €882 million to Nordlink in 2016, €381 million to Neuconnect in 2021 and €300 million to Celtic Link in 2022.

Both mechanisms are explicitly devised to provide incentives for private financing, i.e. to cover part but not all of the financing. This ensures that the interconnection projects respond to a real market demand and that the financing does not generate windfall effects.

Improving revenue flows

The global objective pursued by the European Union and its Member States is to develop interconnections to improve security of supply and affordability of electricity. Traditional TSOs contribute significantly to this objective using their balance sheets but other avenues have been created to allow for private investment to step-in[2].

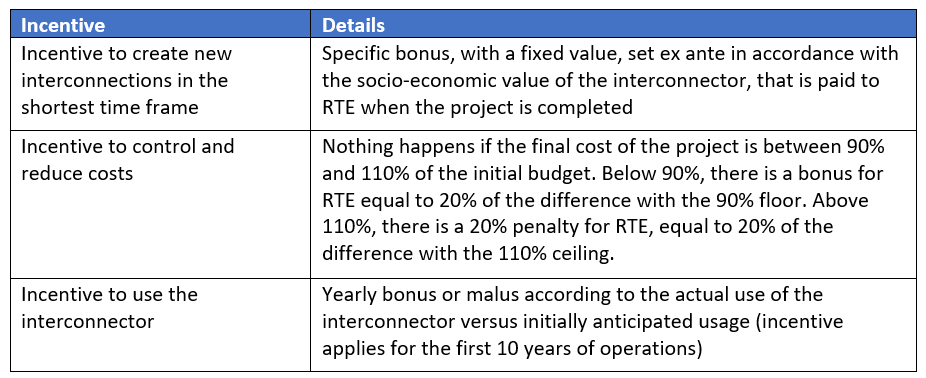

Starting from a common European regulatory framework, very different answers to the financing conundrum have been adopted across Europe. Some jurisdictions, such as France with the Commission de Régulation de l’Energie (CRE), have focused their efforts on the incentive structure of TSOs, improving value both for the TSO and the economy, and strengthening the control on the risks.

SOURCE: CRE Turpe 6 regulation (2021) and 2023 update

This incentive structure provides an economic framework that makes it profitable for the TSO to commit resources to developing new infrastructures. However, it also focuses the build-up effort solely on the balance sheet of the TSOs and raises questions about their ability to raise sufficient equity and debt to undertake all the considered projects, especially when other concurrent priorities must be financed, such as the strengthening of the onshore grid to accommodate renewables and electric vehicles and the development of offshore assets to connect wind farms.

Other regulators, such as Ofgem in the United Kingdom have opted for another regime, mixing the regulated approach with private intervention in an ad-hoc cap-and-floor regime[3]. In this framework, Ofgem guarantees to the interconnector that revenues will remain within a certain corridor over a 25-year period. Should revenues decline below a certain threshold (the “floor”), the interconnector will receive additional compensation payments. Conversely, should revenues exceed a certain amount (the “cap”), the interconnector will have to transfer the excess amounts. Both levels are assessed using a Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model and a target compensation structure.

Allowing additional revenues

There are two streams of additional revenues for interconnectors, beyond congestion charges. Ancillary services provided to the grid such as frequency management for example can provide revenues from the entities responsible for the network management on each side of the border. These services are fairly standard and often do not require specific authorisations beyond the traditional technical certifications and approvals.

Interconnectors can also participate in the capacity mechanisms of the countries they are connecting. In an electricity system where intermittent renewables play an increasing role, having available capacity, even if not used, has intrinsic value. This capacity can be compensated using various mechanisms (strategic reserves, capacity auctions, obligations…) that provide a steady revenue stream to producers that keep spare capacity on the electricity market, even when not operating the plant. Without these compensations, the plants that do not run long enough during the year would close, leaving the electricity system exposed during times of low renewable production. Interconnectors are not power producers, however they do provide additional capacity to the electricity market by allowing for imports. Regulators have then to assess how to value this contribution to the equilibrium of the market. In France, the CRE has decided to allow the participation of interconnections to the capacity mechanism[4].

Interconnections generate socio-economic benefits that are significantly greater than their potential commercial value. This analysis has led to policies actively promoting their development and trying to find innovative ways to increase their ability to find a self-sustained commercial equilibrium despite their significant risk profile. One of the key current issue is the ability of TSOs to finance the new investments on their balance sheet: they must make arbitrages with competing priorities. Private investors are expected to play an increasing role in this equation throughout Europe and, in this respect, the stability and enforceability of the regulatory framework are the most critical incentives.

***

Jean-Baptiste Vaujour is Professor of Practice at the Emlyon Business School

NOTES:

- Looking at MSCI World Core Infrastructure Index (here) as a benchmark in USD and taking Lazard’s Global Listed Infrastructure Equity Fund as anecdotic example in EUR (here). ↑

- See articles on the economics and regulation of the sector (here) and on the example of ElecLink (here). ↑

- Full handbook available here. ↑

- Rules here (in French) ↑