Look at that photo above. Is condensation really responsible for all that moisture you see? We use the term “condensation” a lot when talking about water vapor interacting with materials. But when it comes to porous materials like wood, concrete, and drywall, that’s not really what’s happening. Ready to explore this rabbit hole?

Condensation occurs with nonporous materials

There is some condensation in that photo above. It’s the water dripping off that PVC pipe. Condensation is what happens when a nonporous material drops below the dew point temperature of the air it’s in contact with.

On what kind of materials does condensation occur? Here are a few:

- glass shower door

- mirror (also glass)

- metal window frame

- plastic pipes

- foil jacket on ducts

- porous materials with nonporous coatings like wood with varnish

In cases of true condensation, the water vapor interacts only with the outer layer of the material. And the interaction depends on the temperature of that material. When the material is above the dew point temperature, the surface is dry. When the material drops below the dew point, water vapor molecules stop just bouncing off and start sticking.

Adsorption occurs in porous materials

In the lead photo above, the wood is saturated with water. It started getting wet even before the temperature of the wood dropped below the dew point temperature. Why? Because the water vapor in the air is not just outside the material. It’s also inside the material, floating through the pores and sticking to the pore walls. The relevant psychrometric quantity in this case is relative humidity, not dew point temperature.

![Sorption isotherms for three porous materials [Courtesy of Prof. Chris Timusk]](https://www.energyvanguard.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/sorption-isotherm-porous-materials-chris-timusk-thesis.png)

The type of graph above is called a sorption isotherm, which means sorption (adsorption or absorption) at a constant temperature. This one shows the sorption isotherms for three different porous materials. As you can see, the materials adsorb water molecules as soon as the relative humidity starts increasing from zero and heading to 100 percent.

After a bit, each curve flattens out as the pore surfaces get their initial coverage with water molecules. And then the moisture content of each porous material begins to rise steeply when the relative humidity gets high. That’s when the pores start becoming full of water.

Adsorption vs. absorption

When I wrote the word “adsorption,” that wasn’t a typo. Adsorption (the subject of my doctoral dissertation) is when molecules stick to the surface. In the case of water vapor and porous materials, the water molecules stick to the pore walls, one layer at a time. Those layers have a special name, too: monolayers.

Eventually, though, the pores fill up. Then you have liquid water and the material is now absorbing water.

In my freshman chemistry class, I learned a great way to distinguish between adsorption and absorption. There was a cartoon in my textbook that illustrated this concept with a pie. When someone throws a pie in your face, you’ve adsorbed it. When you eat a pie, you’ve absorbed it.

Understanding sorption isotherms

Now, back to the sorption isotherms. That steep rise at high relative humidity doesn’t depend on the dew point temperature. Instead, it depends on how big the pores are, the shape and distribution of the pores, and the relative humidity. This rabbit hole is a deep one, but if you want to understand things like buckling floors, wet sheathing, and mold, you may want to jump in.

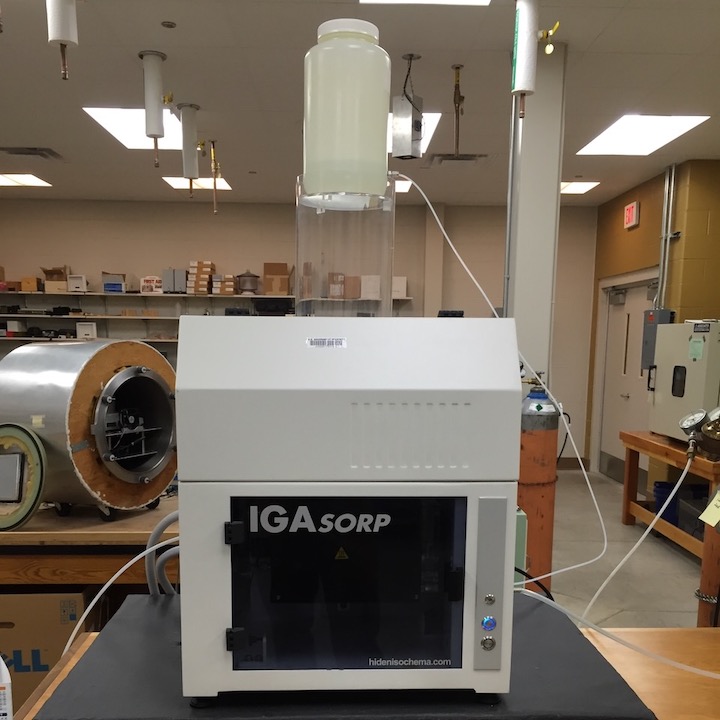

As you can see in the sorption isotherm graph above, each material has its own shape when you plot this graph. The way building scientists create sorption isotherm graphs is with carefully controlled experiments with equipment like you see above.

They put a sample in the chamber. It sits on a scale that measures the mass. They gradually increase the relative humidity inside the chamber while maintaining a constant temperature (iso = same, therm = temperature). The mass increases as the relative humidity increases. Then they plot the data.

Temperature variation

Now let’s talk about temperature. Each sorption isotherm is measured at a constant temperature. But what happens when we measure sorption isotherms for the same material at different temperatures? It’s what we expect would happen, right? As we lower the temperature, the material absorbs more water.

![Moisture content of wood at different temperatures and relative humidity [Source: Forest Products Laboratory, Research Note FPL-RN-0268]](https://www.energyvanguard.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/moisture-content-wood-vs-relative-humidity.jpg)

The table above comes from a US Forest Products Lab paper on the equilibrium moisture content of wood and illustrates this principle. As you go from lower to higher relative humidity, the moisture content increases. And as you go from the bottom to the top at each relative humidity, the temperature drops and the moisture content increases. (Hat tip to JayW for providing this resource in the comments below!)

Down the rabbit hole

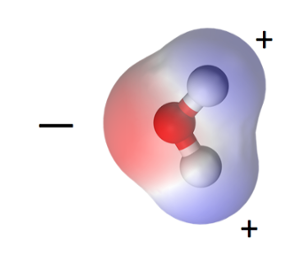

I discussed this topic in my book, but let’s take a quick look here, too. The water molecule, one oxygen and two hydrogens, is polar. The oxygen lacks two electrons from having a complete outer shell. The hydrogen has one electron in its outer shell and would like one more. So the oxygen shares one electron with each hydrogen by creating covalent bonds. That makes the oxygen side slightly negative, the hydrogen side slightly positive.

This polarity has enormous ramifications for how water interacts with materials. In fact, it has enormous implications for life on Earth. It’s this polarity that affects how it interacts with materials. That applies to what’s going on inside the pores of porous materials and on the surface of nonporous materials.

Want to go deeper? See chapter 6 of my book. Also, these two articles by Dr. Joseph Lstiburek can open up whole new pores in this rabbit hole:

It’s All Relative

Wood Is Good…But Strange

But the big takeaway here is that when we’re talking about porous materials, it’s not really condensation that’s happening. The term I like to use is moisture accumulation. And now that you’ve got this under your belt, you’re ready to join the building science nerds who argue about whether or not you can get condensation on a sponge.

____________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can subscribe to the Energy Vanguard newsletter and follow him on LinkedIn. Images courtesy of author, except where noted.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.