Onshore wind turbines have a permitting problem in the U.S. and Europe. One main complaint from homeowners is that they believe the sight of a turbine will reduce their property value. Maximilian Auffhammer at the Energy Institute at Haas describes his co-authored published study that tests this assumption. The study looks at sale prices of over 300m homes in the U.S. within 10km of a turbine, sold between 1990 and before COVID hit. The clever bit is it specifically compares sale prices of neighbouring houses (sold at the same time), where one house cannot see the turbine (due to an obstruction like a hill). The average home that has sight of a wind turbine sold for 1.2% less than an identical home that does not, which is small enough to be a rounding error. Though properties within 1.5km reveal a higher margin (8%), they are rare: only 0.03% of the sample (within the 10km radius) are so close to a turbine. Most importantly, the negative impact of seeing a wind turbine disappears over time: turbines installed in the past decade had a much smaller effect on prices, indistinguishable from zero in recent years. People – specifically buyers of homes – are getting used to it. As Auffhammer says, when electricity pylons first appeared many decades ago they were considered ugly but now home buyers hardly care. Note that a 500ft (150m) wind turbine one mile (1.6km) away would appear to be the size of a golf ball held at arm’s length.

Onshore wind turbines have a permitting problem in the U.S. and Europe. One main complaint from homeowners is that they believe the sight of a turbine will reduce their property value. Maximilian Auffhammer at the Energy Institute at Haas describes his co-authored published study that tests this assumption. The study looks at sale prices of over 300m homes in the U.S. within 10km of a turbine, sold between 1990 and before COVID hit. The clever bit is it specifically compares sale prices of neighbouring houses (sold at the same time), where one house cannot see the turbine (due to an obstruction like a hill). The average home that has sight of a wind turbine sold for 1.2% less than an identical home that does not, which is small enough to be a rounding error. Though properties within 1.5km reveal a higher margin (8%), they are rare: only 0.03% of the sample (within the 10km radius) are so close to a turbine. Most importantly, the negative impact of seeing a wind turbine disappears over time: turbines installed in the past decade had a much smaller effect on prices, indistinguishable from zero in recent years. People – specifically buyers of homes – are getting used to it. As Auffhammer says, when electricity pylons first appeared many decades ago they were considered ugly but now home buyers hardly care. Note that a 500ft (150m) wind turbine one mile (1.6km) away would appear to be the size of a golf ball held at arm’s length.

Don Quixote and NIMBYs have spent significant energy fighting windmills (technically wind turbines in the case of the energy-producing kind). This resistance continues to be a major bummer for advocates of the fastest growing (and may I add clean, low cost and ample) renewable energy in the United States.

There are a number of arguments put forward against wind turbines. According to critics, they are noisy, cause a visual flicker for some homes during certain times of the day, and kill birds. I am not even going to go after the ridiculous whale thing. One additional argument that has been put forward is that they are just ugly things that destroy our visual enjoyment of this land. These are all interesting assertions, but some of these are testable! And so we did.

Does sight of a turbine lower property prices?

In a paper out last month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Wei Guo, Leonie Wenz and I test whether housing values for homes that can see a wind turbine, versus homes nearby that can’t because of an obstruction in the landscape (think a hill) fetch lower sales prices when sold. What is cool about this exercise is that we did this for all wind turbines in the US using transactions for more than 300 million homes.

The intuition is simple. Meredith and David live next door to each other. In identical homes. The only difference is that out her living room window, Meredith can see a 500 foot tall wind turbine and David cannot because a hill is in the way. Both sell their home at identical times. The difference in sales price is hence the effect of seeing the wind turbine (labour economists, control your urges to tell me what other things the hill might be doing). We do this exercise for all homes within 10 kilometers of a wind turbine that were sold between 1990 and before COVID hit.

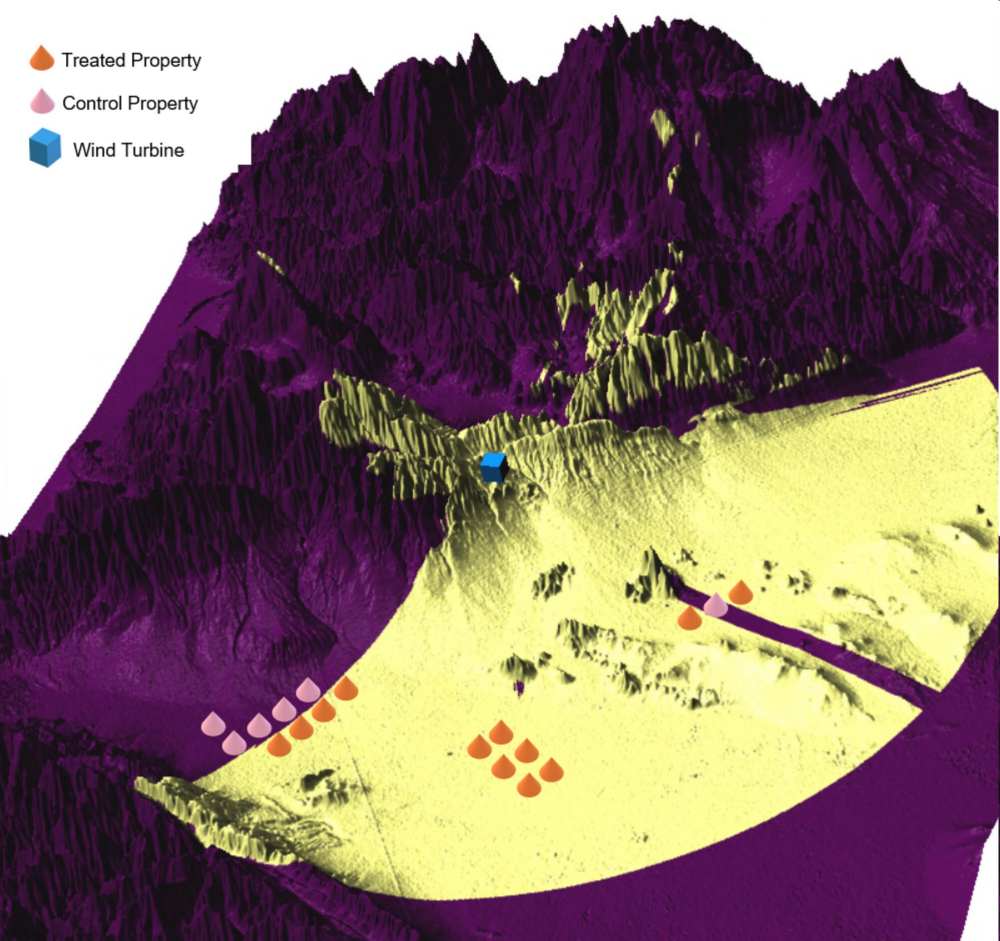

The figure below shows you what we did for each wind turbine. When you think about how many wind turbines there are in the U.S., you can imagine that this nearly melted a few computers. The blue cube is a wind turbine. The orange blobs are homes that can see the wind turbine. The pink blobs are homes that can’t. Now we compare sales prices for orange and pink blobs.

Findings

What do we find, you ask?

- The average home in the sample that has a wind turbine in its viewshed sold for 1.2% less than an identical home that does not. Is this a lot? It’s not peanuts. We estimate about 25 billion dollars over the three decades we are looking at. But compared to the multi-trillion dollar value of housing assets, this is rounding error.

- Homes closer to wind turbines have larger impacts. The visual disamenity (think mental/emotional response to finding something ugly) reduces property values by up to 8% within a neighbourhood range of 1.5 km (0.9 miles). However, the number of properties within this distance is small. Nationally, there are fewer than 250,000 transactions within 1.5 km of the nearest wind turbine, as opposed to approximately 8.5 million transactions within 10 km. As we move further away from a turbine, the effect is statistically indistinguishable from zero when 8 km (5 miles) away from the nearest wind turbine. To put this in perspective, if one stretched out an average-sized arm and held up an aspirin tablet, this would equate the perceived size of an average wind turbine five miles away. Were the same wind turbine one mile away, it would appear to be roughly the size of a golf ball. (Max is very proud of figuring this out).

- We further investigate what drives the visual disamenity effect. We find that the negative impact of wind turbines on property values is primarily observed among urban properties, with negative but noisy effects in rural areas. Our analysis based on geographical altitude suggests that the negative impact of wind turbine visibility is particularly pronounced in non mountainous regions. We also observe a strong correlation between local political leanings and disamenity effects, with right-leaning communities experiencing a significantly greater impact compared to left-leaning areas. Last, the visual disamenity is more accentuated in high-income locales as opposed to low-income areas. So rich, conservative urban flat areas dislike wind turbines the most.

- Most importantly, thank you referee 3, we found that the negative impact of seeing a wind turbine disappears over time. There is a much bigger effect on nearby housing values right after a wind turbine is constructed than a few years later. But most importantly, if we look at whether the estimated effect changes over time, we find- no matter how we slice it – that wind turbines installed in the past decade had a much smaller effect, so much smaller that it is indistinguishable from zero in recent years. WOW. ZA. ZOOEY. What this implies is that we probably get used to seeing wind turbines. I bet you that the first transmission tower was hated as much as the first wind turbine. But frankly, I do not even notice transmission infrastructure anymore. I got used to it!

So in summary, we show that wind turbines do not seem to negatively affect housing values (on average) any more. While “nothing to see here” is usually a deadly finding for an academic, this is an important zero, as it strengthens the positive case for building more of these sources of clean electricity.

But what about the bad news Max? I do not come here for good news. OK, I’ll indulge. You know what kills birds? CATS! According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service, land-based wind turbines kill about 250,000 birds per year. Cats: 2.4 billion. So NIMBY Person, put down the protest sign, recall your lawyer and lock up your cat. We’ll all be better off for it.

***

Maximilian Auffhammer is the George Pardee Professor of International Sustainable Development at the Energy Institute at Haas, part of the University of California, Berkeley.

This article is published with permission

Keep up with Energy Institute blogs, research, and events on Twitter @energyathaas